The deprivation-related sport gap

Exploring why people who live in more deprived areas are less likely to take part in sport and physical activity.

Scotland has a deprivation-related sport and physical activity gap.

All views, analysis, and summaries in this post are my personal work and opinions. The R code for my data wrangling and plots can be found on GitHub.

This problem isn’t unique to Scotland, there are examples of poverty-related sport/physical activity gaps across the globe. Each country will have it’s own unique challenges but some potential barriers (and solutions) may also be universal.

The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) is an index of relative deprivation. It sections Scotland into around 7k datazones with roughly equivalent population sizes. These areas are then ranked against 7 risk domains (access to services, crime, education, employment, health, housing, income) and divided into quintiles. Areas that rank highest against multiple domains are described as the most deprived areas of Scotland (quintile 1).

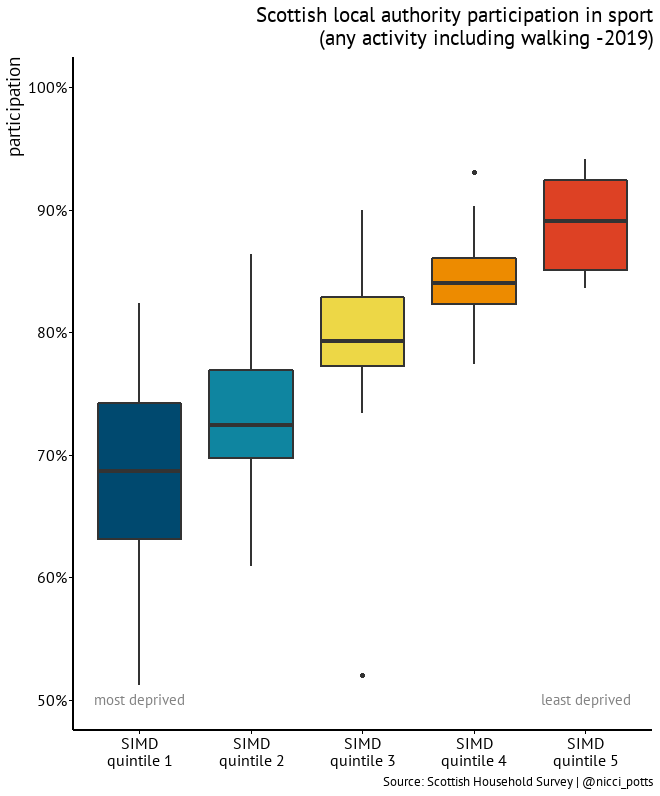

Data from the Scottish Household Survey shows us:

- There is a correlation between increasing SIMD quintile and increasing sport/physical activity participation (i.e. decreasing levels of deprivation leads to increasing participation in sport/physical activity).

- Those that live in the most deprived areas of Scotland (SIMD quintile 1) are less likely to participate in sport/physical activity compared to those in the least deprived areas (SIMD quintile 5).

While poverty does not equal deprivation, there are strong ties between those who are on low-incomes living in areas of high deprivation. This makes the leap to financial barriers to participation a small one to make.

Undoubtedly finances are a barrier to sport/physical activity participation. Sport and physical activity are not free. People will regularly claim going for a run costs nothing. They are wrong. If you want to do any outdoor activity in Scotland 12 months of the year, multiple times a week, you need to invest in some gear (especially waterproofs!). The only potential exception to this is walking.

Walking up hills or mountaineering is certainly not free but going for a walk around your neighborhood or local park does not require the same financial investment as other activities. So why then is there a big difference in participation between the most and least deprived areas?

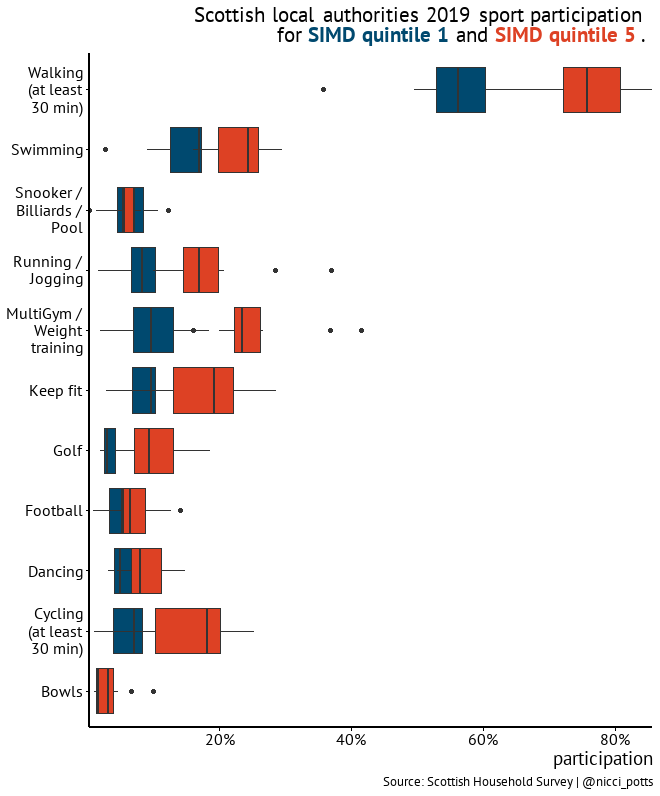

It is not unsurprising to see the breakdown of individual activity participation also show differences between SIMD quintiles, however;

- Not all sport/activities show a significant difference between SIMD quintile 1 and SIMD quintile 5 participation (bowls and snooker for example).

- There isn’t a difference between traditionally indoor or facility based sports (swimming, golf, bowls, gym) and outdoor sports (football, running, cycling).

- The biggest absolute difference is in walking (the biggest proportional differences are golf, running, then walking).

As walking participation is so high for both SIMD quintiles, increasing SIMD quintile 1 participation to match that of SIMD quintile 5 would pretty much eliminate the deprivation-related physical activity gap.

So the solution is to get people more walking.

Well, not quite! By saying we need to get more people walking we place the onus on the individual. Interventions or campaigns to highlight the benefits of sport/physical activity aim to educate/inspire individuals to encourage their participation, but do they consider external factors? (i.e. the barrier isn’t with person but with the circumstance!).

I wanted to test a hypothesis;

People who live in areas of higher deprivation have:

- less access to green space

- increased problems in their neighborhoods.

which discourages participation in walking.

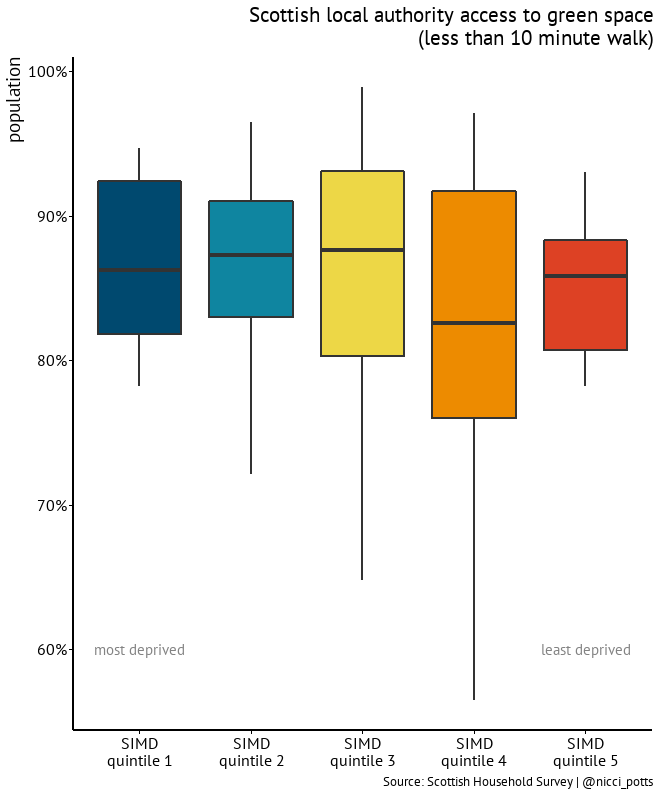

On my first point, I was wrong.

- The majority of people across all SIMD quintiles have less than a 10 minute walk to a green space.

- While there is variation across the local authorities, the lowest values are in SIMD quintile 4 (which has high walking participation).

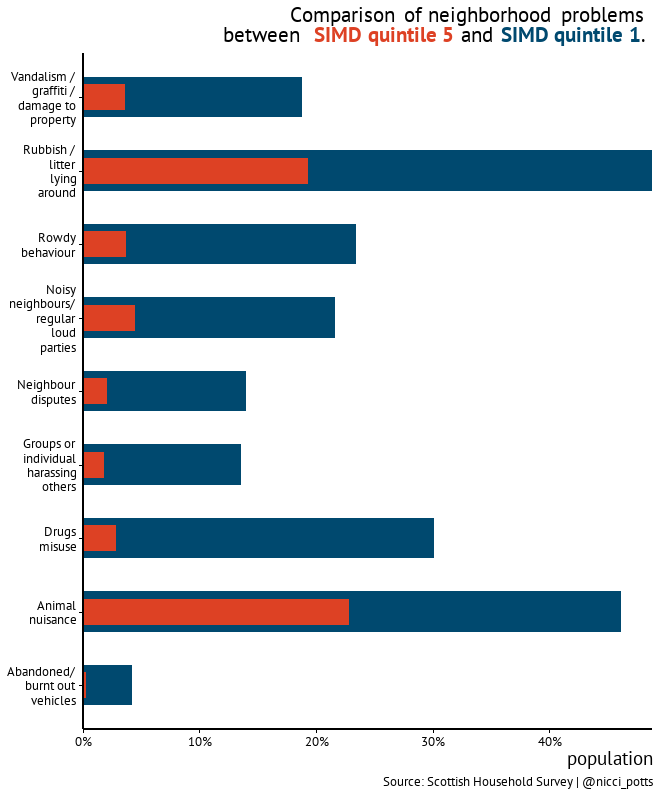

But on my second point, I was correct.

- More people in SIMD quintile 1 report problems in their neighborhoods compared to those who live in SIMD quintile 5. (i.e. there are more problems in more deprived areas).

- Rubbish and animal nuisances are fairly common in both SIMD quintiles but there are greater amounts of vandalism, rowdy behavior, drugs, and harassment in SIMD quintile 1. (i.e. the problems which are more likely to make a person feel unsafe are proportionally larger in more deprived areas).

In addition, in 2019 8% of people in the most deprived areas had experienced harassment (10% discrimination) compared to 5% of people in the least deprived areas (6% discrimination).

So how does this impact on people’s ratings of their neighborhoods?

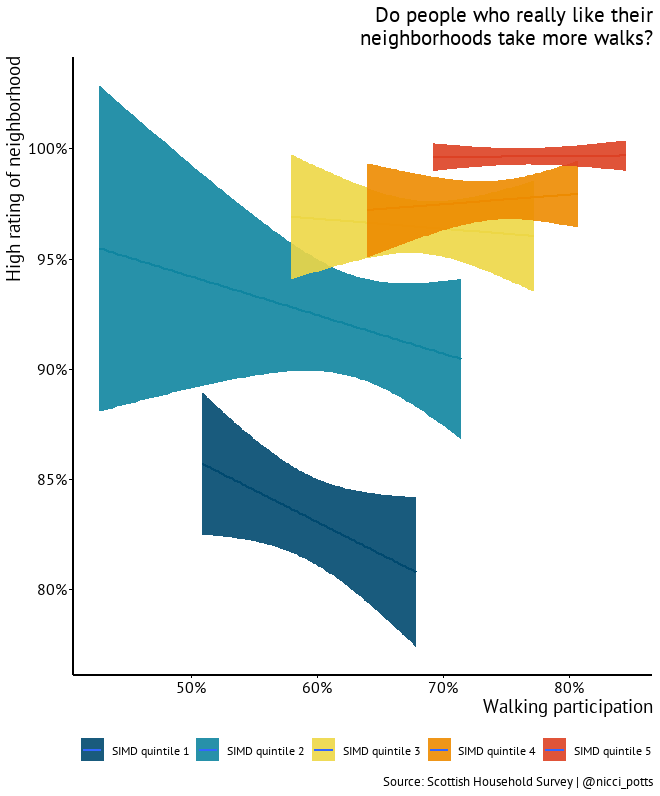

- People who live in SIMD quintile 5 (least deprived) are more likely to rate their neighborhoods as ‘very/fairly good’ compared to those who live in SIMD quintile 1 (most deprived).

- And so there is a correlation between increasing rating of neighborhoods as ‘very/fairly good’ and increased walking participation.

- The biggest variation in high neighborhood ratings, across local authorities, is in SIMD quintile 2 with decreasing variation to SIMD quintile 5 (i.e. people in SIMD quintile 5 unanimously rate their neighborhoods highly compared to the other SIMD quintiles.)

However, 85% of the SIMD quintile 1 population still rate their neighborhoods as ‘very/fairly good’, with only 4% rating their neighborhoods as very poor. That’s an overwhelming majority of people rating their neighborhoods highly!

With the data suggesting that while people living in the most deprived areas are more likely to have experienced harassment/discrimination, as well as, problems in their neighborhood, they are also less likely to let this impact their rating of their neighborhood as a place to live.

As 8.5 out of 10 people from SIMD quintile 1 rate their neighborhoods as ‘very/fairly good’ and 6 out of 10 people take part in walking, there are still people who rate their neighborhoods highly that don’t participation in walking.

Let’s throw something else into the mix; in the UK people on low incomes are more likely to work non-standard hours (compared to those on higher incomes). They are also more likely to have care commitments, work multiple jobs, and have less access to childcare (Caroline Criado Perez covers this really well in her book Invisible Women).

28% of those in most deprived have no childcare compared to 10% least deprived. Of those in the most deprived areas 50% use local authority nurseries for childcare (34% least deprived). While 48% of the least deprived use private nursery provision (13% most deprived).

So now take those problems that are more likely to be met in the most deprived areas, then add evenings, nighttime, or early mornings. My assumption would be people are less likely to use parks for recreation or walk the streets late at night/in the dark, especially if they have experienced or witnessed problems in their area!

So what does this mean for sport and physical activity?

If we want people to utilize community space more, does this have to come hand-in-hand with other measures to reduce anti-social behavior? (does an increase in people using their neighborhoods for leisure lead to a reduction in anti-social behavior?) And do those measures have to work on a 24hr clock rather than targeting peak times based on a standard 9-5 schedule?

I looked specifically at walking here but the same deprivation-gap exists for other sports. Do leisure facilities and sport clubs cater for people who work non-standard hours?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that “up to 5 million deaths a year could be averted if the global population was more active”.

Of course, people who live in high areas of deprivation are not a homogeneous group and there are a multitude of potential barriers to participation. However, there is an uncomfortable truth that systems with inherent deprivation-related inequalities have evolved to serve a more privileged society. If we have systems with historically under represented groups, then those system have historically not been designed, built, and/or evolved with under represented groups in mind, by default.

Maybe by diversifying participation in sport/physical activity the system will itself, over time, evolve to reflect the diversifying needs of all subsets of society. But would we see quicker reduction of inequality gaps by adapting the system for the individual, rather than the individual adapting for the system?